She shifted her weight. “Is it…good?”

“Good?” I laughed, half-hysterical. “MIT is one of the best science schools in the world. They don’t just send letters like this for fun. They noticed you. They want you to apply.”

She took the letter from my hands, eyes scanning slowly. Her lips moved as she read, sounding out the words under her breath the way she always did with dense text. Then she whispered, almost offhandedly, “But I’m the dumb one. Grandpa said so.”

Something inside me broke.

“You are not dumb,” I said fiercely. “You never were.”

“Then why does everyone think I am?” she asked, and there was no anger in her voice, just tired confusion.

“Because they don’t understand dyslexia,” I said. “They see you struggling with reading and they think it means you’re not smart. They don’t see how hard you work. They don’t see the way your brain lights up when you talk about water filtration. They don’t know about your poems or your competition or this letter. That’s on them, not on you.”

She looked at the letter again. “Do you think I could get into the program?” she asked.

“I think you can do anything you set your mind to,” I said. And for once, it didn’t feel like a platitude. It felt like a simple statement of fact.

We filled out the application that night. She wrote essays—again dictating most of the words while I typed, because I refused to let her dyslexia turn a doorway into a wall. She described her project, her love for environmental science, her curiosity. She talked about dyslexia too, about how it forced her to break problems down differently. We hit submit the next day.

Two days later, my parents called.

“Victoria,” my mother said, voice bright, “we’re planning our anniversary party. Forty years. Can you believe it?”

I made a noise somewhere between a laugh and a sigh.

“We want to make a big announcement,” she continued, “about our estate planning. We’ve decided who will be inheriting the house and the trust fund. It will be a beautiful moment. Very meaningful.”

My stomach dropped. “What kind of announcement?”

“Well, Sophia’s been doing so well,” my mother said. “Straight A’s, piano, leadership roles at school. We’ve decided to leave the family home and the two hundred and fifty thousand dollar trust fund to her.”

I gripped the phone tighter. “And Emma?”

“We’ll leave her some money, of course,” my mother said. “Maybe twenty thousand. Enough to help her get started in whatever simple career she chooses.”

Twenty thousand versus two hundred and fifty thousand. One child as the primary heirs to the “legacy,” the other tossed a consolation prize. My throat burned.

“Mom,” I said slowly, “Emma is not—”

“We’ve made our decision,” she interrupted. “It’s what’s fair.”

Fair. They misused that word as effortlessly as they misused dumb.

After we hung up, I sat at the kitchen table staring at the wall until the sunset outside turned everything orange.

I almost didn’t go to the party. I almost told them to enjoy their celebration without us, to give their speech without my daughter sitting in the corner absorbing every word like poison. But something inside me refused. It felt wrong to absent Emma from a story about her, even if that story was cruel. It also felt wrong to let that story be the only one.

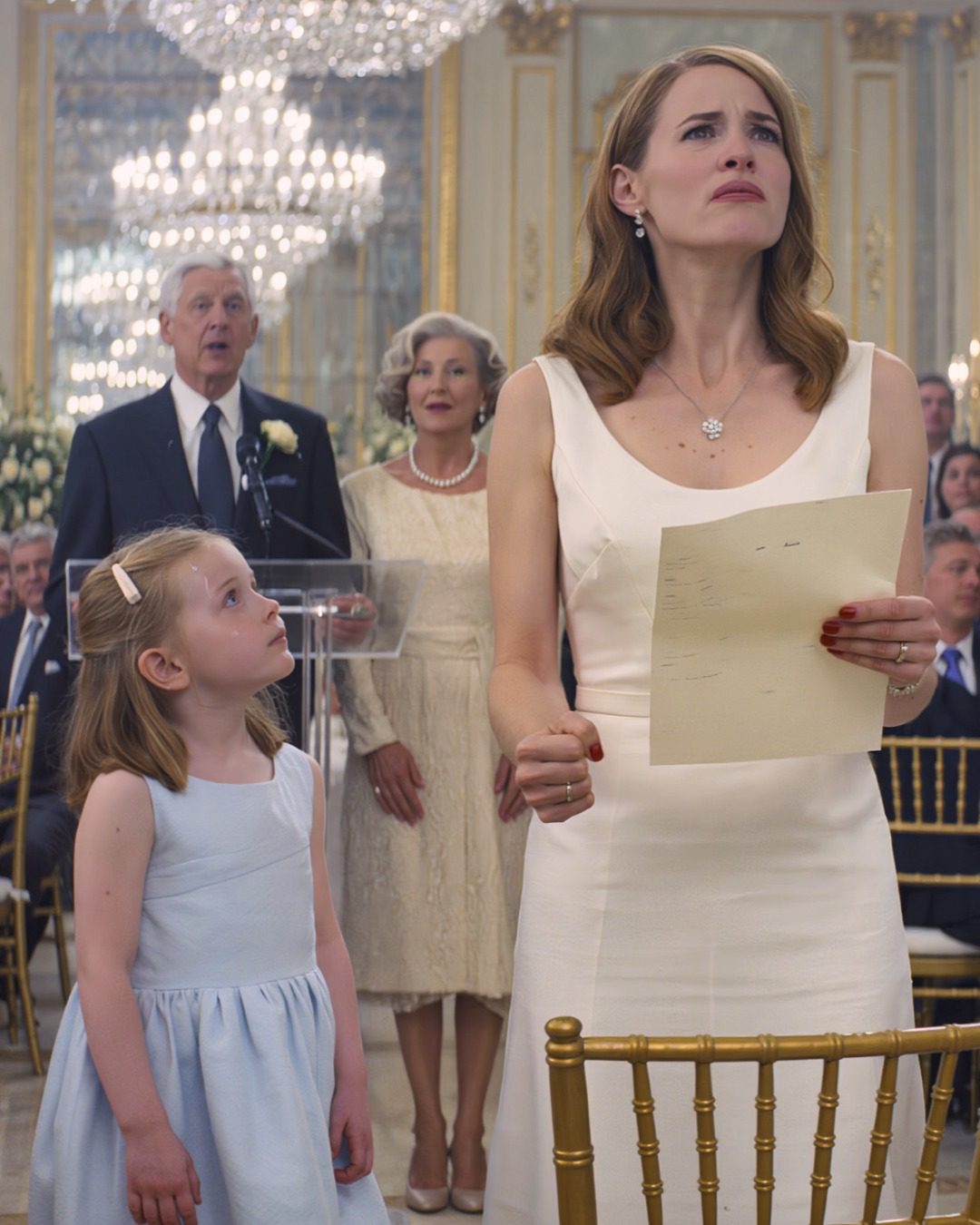

So we went. She wore her blue dress. She plaited her hair herself, hands clumsy but determined.

“Are you okay going tonight?” I asked as we drove. The city lights blurred past her window.

She shrugged. “I don’t really want to see Grandma and Grandpa,” she admitted. “But I want to see Sophia.”

I appreciated her honesty. “If at any point you want to leave, you tell me,” I said. “We’ll go, no questions asked.”

“Even if it’s in the middle of the party?” she asked, a small smile tugging at her mouth.

“Especially then,” I said.

Back in that ballroom, after my father’s speech and Emma’s flight to the bathroom, I stood holding a champagne glass, the weight of years pressing against my ribs.

“I have an announcement too,” I’d said to the room. Fifty faces turned toward me.

I pulled my phone from my purse first. On the screen was a photo of Emma standing beside her homemade filtration system, goggles on, grin huge, shoulders squared with quiet pride. I held it up.

“Last year,” I said, “Emma entered the National Youth Science Competition. On her own, she researched, designed, and built a water filtration system that removes ninety-eight percent of contaminants using recycled materials. Out of five thousand entries nationwide, she placed third.”

A murmur rippled through the crowd. My parents’ faces went pale.

“She also writes poetry,” I continued, swiping to screenshots of digital magazines. “Beautiful poetry. Three of her poems have already been published in literary magazines. At twelve years old.”

I turned to face my sister. “Sophia is talented. No one is denying that. She works hard, and she deserves every bit of praise she gets. But Emma is not dumb. She is dyslexic. There is a difference.”

My mother opened her mouth, eyes watery. “We didn’t know—”

“You didn’t know because you never asked,” I said. “You never looked past your idea of who she is. You just labeled her and moved on.”

Finally, I pulled out the folded letter that had been burning a hole in my purse all evening. The MIT letter.

“And last week,” I said, my voice suddenly thick, “Emma received this.”

I held it up.

“This is from MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” I said, in case anyone in the room somehow hadn’t heard of it. “They saw her science project and were impressed enough to invite her to apply to their new summer program for gifted young scientists. The program is for kids ages twelve to fifteen. My daughter is the youngest age eligible, and they want to see more from her.”

Gasps. Whispers. A few people exchanged looks that clearly said, We had no idea.

“Emma is not the dumb one,” I said. “She has dyslexia, which means reading is hard. It means she has to work twice as hard as other kids just to read a page of text. But she does it. And beyond that, she’s curious and creative and determined. That is what intelligence looks like. That is what you’ve refused to see.”

I met my parents’ eyes. My father looked like someone had punched him. My mother was openly crying now, mascara smudging beneath her eyes.

“We’re sorry,” she whispered. “We didn’t understand.”

“You didn’t want to,” I replied. “It was easier to compare her to Sophia, to pick a favorite, to write Emma off as destined for a ‘simple’ life.”

Rachel shot to her feet, her chair scraping loudly. “Victoria, this isn’t the time for this,” she snapped. “You’re ruining their party.”

“When is the time?” I asked. “After you’ve collected your inheritance? After Emma spends her entire childhood thinking she’s worthless because the people who are supposed to love her unconditionally decided she wasn’t worth investing in?”

No one answered.

I took a breath, feeling my hands shake. “Keep your trust fund,” I told my parents. “Keep your house. Emma doesn’t need it.”

My father frowned. “Don’t be ridiculous,” he said. “This is for Emma’s future.”

“She’s going to build her own future,” I said. “With or without your money. What she needed—what she still needs—is your respect. Your belief in her. And you have failed her in that more than any inheritance could ever fix.”

I set the champagne glass down. The clink against the table sounded final.

Then I walked away.

Down the hallway, I found the bathroom door closed. I knocked gently. “Emma? It’s Mom.”

There was a muffled sniffle. “Go away.”

“I will if you want me to,” I said, leaning my forehead against the door. “But I just told everyone the truth about you. About your science project. About your poems. About MIT.”

Silence. Then the sound of the lock turning.

The door opened a crack and one red-rimmed eye appeared. “You told them?” she asked, voice small.

“I told them,” I said. “I told them everything. And then I told them to keep their money.”

She opened the door wider. “You what?”

“I’ll explain in the car,” I said softly. “If you’re ready to go.”

She nodded. Tears still streaked her cheeks, but there was a spark in her eyes that had not been there when she ran away from the table.

We walked back through the ballroom. The music had started up again, but it felt wrong, too cheerful for the air now filled with tension and hushed conversations. My parents called after us. My father’s voice trembled. “Victoria, please. Let’s talk about this.”

I didn’t turn around.

We stepped out into the cool night air. My hands shook as I fumbled with the keys, but once we were in the car and the doors were closed, a strange quiet settled over us.

“Mom,” Emma said after a few minutes of driving, her voice tentative. “Did you mean all that stuff? About me being smart?”

I pulled the car over to the side of the road and put it in park. Then I turned to her fully.

“Every single word,” I said. “Emma, you are brilliant. Not because of MIT or competitions or publications. Those things are wonderful, but they’re just reflections of something that’s already there. You’re brilliant because of the way you think, the way you care, the way you keep going even when things are hard.”

She looked unconvinced. “But I have dyslexia,” she said. “I can’t read like other kids.”

“Dyslexia doesn’t make you dumb,” I said. “Some of the smartest people in history had dyslexia. Albert Einstein. Thomas Edison. Steven Spielberg. They struggled with words on a page, but that didn’t stop them from changing the world.”

She stared out the window for a moment. Then she said quietly, “I got into the MIT program.”

For a second I thought I’d misheard. “What?”

“The email came this morning,” she said, turning back to me. Her eyes were bright now, almost glowing. “I didn’t want to tell you until after the party. I thought maybe it could be good news if…if tonight was bad. I got in, Mom. They want me.”

All the air rushed out of my lungs. “You—you got in?” I stammered. “And you were just going to sit through that dinner with that secret in your pocket?”

She shrugged. “I wasn’t sure. I still thought maybe I didn’t deserve it. Because, you know…dumb one.”

A sound came out of me that was half laugh, half sob. I unbuckled my seatbelt, leaned across the console, and wrapped my arms around her.

“I am so, so proud of you,” I whispered into her hair. “I don’t care what my parents think. I don’t care about their party or their money. You did this. You earned this. MIT wants you, and so do a thousand problems in the world that need your brain.”

She hugged me back, tightly. We stayed like that for a long time while the car’s hazard lights blinked in the darkness like a slow, steady heartbeat.

In the days that followed, my parents called. A lot.

I ignored every ring. My voicemail filled with messages.

“Victoria, please, we need to talk.”

“You overreacted.”