“We didn’t mean it that way.”

“Of course we’re proud of Emma.”

“We’ve rethought everything. Call us back.”

I didn’t.

A week later, they showed up at my house.

Emma was at school when the doorbell rang. I nearly didn’t open the door, but curiosity won out over the urge to pretend I wasn’t home.

My parents stood on the porch looking older than I’d ever seen them. My mother’s makeup was minimal, eyes puffy. My father’s shoulders were slightly slumped, as if someone had deflated him.

“May we come in?” he asked.

For a long moment I considered saying no. Then I stepped aside.

We sat at the kitchen table—the same table where Emma and I had celebrated her victories, where she’d written poems and filled out applications. It felt like neutral ground and home turf all at once.

“We’re so sorry,” my mother began, her voice breaking. “We had no idea Emma was so…accomplished.”

“You would have known,” I said, “if you’d paid attention. If you’d asked about her instead of using her as a measuring stick to make Sophia look taller.”

My father winced. He took an envelope from his jacket and slid it across the table toward me. “We’ve revised our estate plan,” he said. “We’re splitting everything equally between the girls now. The house, the trust fund, all of it. That’s what’s fair.”

I didn’t even open the envelope. I pushed it back toward him.

“Emma doesn’t want it,” I said.

My mother’s mouth fell open. “What? Don’t be ridiculous. Of course she does.”

“She doesn’t need your money,” I said. “She needs your respect. Your love. Your belief in her. You can’t buy back the years you spent calling her slow, implying she was destined for less. That damage won’t vanish because you adjusted some numbers in a lawyer’s office.”

“How do we fix this?” my mother whispered. Her voice held something I hadn’t heard directed at me in a long time: genuine humility.

I sighed. I’d had a week to cool down, but some anger still simmered. Underneath it, though, was something else: a reluctant hope. Not for my sake. For Emma’s.

“Start by learning what dyslexia actually is,” I said. “Read about it. Not in order to argue or minimize, but to understand. Go to a workshop. Talk to a specialist. Stop treating it like a synonym for stupidity.”

My father nodded slowly. “We can do that,” he said.

“And then,” I continued, “apologize to Emma. Really apologize. No excuses. No ‘we didn’t mean it that way.’ Tell her you were wrong. Tell her she is brilliant. And then accept that she may not forgive you quickly. Rebuilding trust will take years, not weeks. You don’t get to rush her because you’re uncomfortable with the consequences of your own actions.”

My mother wiped her eyes. “We’ll do anything,” she said. “We…I don’t want to lose my granddaughter.”

“That’s not up to you anymore,” I said softly. “That’s up to her.”

They left the envelope on the table even after I tried to hand it back a second time. I eventually put it in a drawer. Not as a backup plan for Emma, but as a reminder that some things cannot be fixed with money.

Right now, as I tell this story, Emma is at MIT.

She got into the summer program. She was the youngest student in her cohort. The first day we arrived on campus, she clutched her suitcase handle so tightly her knuckles went white. We stood in the shadow of those historic buildings, surrounded by teenagers with lanyards and backpacks, and I saw her eyes widen as she took it all in.

“Do you think I’ll fit in here?” she whispered.

“I think you belong here,” I said. “Whether you feel it right away or not is another story. But you belong.”

We checked her into her dorm. Her roommate was fifteen, tall and confident, talking excitedly about coding projects and robotics competitions. For a moment, Emma looked like she might shrink back into herself. Then the roommate spotted the water filter prototype peeking out of Emma’s bag and said, “Whoa, is that the project you did? That’s so cool. Tell me about it.”

I watched my daughter’s shoulders straighten. “Well,” she began, “it started because I read about how many people don’t have clean water…”

That night, after I hugged her goodbye and walked back to the car alone, my phone buzzed. A text from Emma.

The letters on the signs here still dance sometimes, she wrote. But it’s okay. I think I’m dancing with them now.

She calls me most evenings. Her voice comes crackling through the line full of excitement.

“Today we learned about membrane filtration!”

“I met a professor who works on water purification systems in developing countries!”

“We ran tests in the lab and my results were actually really close to what our mentor expected!”

“I read an article today and only had to re-read each paragraph twice instead of five times!”

Sometimes she tells me about the other kids: a boy who builds electronics from scrap metal, a girl who writes code like poetry. For the first time, she’s in a place where being different isn’t a liability. It’s assumed.

My parents are trying.

They started with books. They went to the library and checked out everything they could find about dyslexia. My mother called one day to tell me, voice trembling, “Did you know that many people with dyslexia have average or above-average intelligence? That they often excel in creative problem-solving?” I bit back the urge to say, I told you that years ago. Instead, I said, “I’m glad you’re learning.”

They attended a workshop at a local education center. They sit in therapy once a week now, confronting their bias, their favoritism, the way they equated traditional academic success with worth. It’s not pretty. But change rarely is.

They sent Emma a card last week. It arrived in a plain white envelope, the handwriting familiar and shaky.

Dear Emma,

We were wrong. About dyslexia. About you. We let our old-fashioned ideas about intelligence blind us to how extraordinary you are. We are learning, and we are so proud of you. We hope, in time, you can forgive us. Love, Grandma and Grandpa.

Emma las het aan de keukentafel toen ze in het weekend tussen twee programmasessies thuis was. Eerst zei ze niets. Ze volgde de woorden alleen met haar vinger, haar lippen op elkaar geperst.

‘Wat vind je ervan?’ vroeg ik zachtjes.

Ze haalde haar schouders op, maar er verscheen een lichte glimlach in haar mondhoek. « Het is een begin, » zei ze.

Vervolgens stopte ze het kaartje in haar dagboek, tussen pagina’s vol gekrabbelde dichtregels.

Ik weet niet precies hoe hun relatie zich vanaf nu zal ontwikkelen. Misschien zit ze op een dag met hen op de bank en praat ze over waterfilters, gedichten en programma’s, en luisteren ze met dezelfde aandacht die ze vroeger alleen voor Sophia hadden. Misschien zullen sommige wonden nooit helemaal helen. Misschien komt vergeving geleidelijk in plaats van in één keer.

Wat ik wél weet is dit: mijn dochter gelooft niet langer dat zij de domste is.

Ze weet nu dat anders zijn niet hetzelfde is als tekortschieten. Dat moeite hebben met lezen niets afdoet aan haar scherpe geest. Dat intelligentie geen smalle gang is, maar een uitgestrekt huis met vele kamers, en dat ze sleutels heeft van meer dan één.

Toen ze zeven was, voelde het woord dyslexie als een straf. Op haar twaalfde voelde het als iets waarvoor ze zich moest verontschuldigen. Nu, op de drempel van kindertijd naar adolescentie, voelt het meer als een lens – een manier om zichzelf te begrijpen die gepaard gaat met uitdagingen, jazeker, maar ook met sterke punten.

Ze is nog steeds hetzelfde meisje dat ooit aan een kindertafel zat en probeerde onzichtbaar te worden. Maar ze is ook het meisje wiens wetenschapsproject de aandacht trok van een van de beste universiteiten ter wereld, die gedichten schrijft over rivieren en veerkracht, die in een beroemd laboratorium stond en dacht: hier hoor ik thuis.

Mijn ouders keken ooit naar haar en zagen een tekortkoming. Ik kijk naar haar en zie een heel universum.

En als er één ding is dat ik wil dat iedereen die dit verhaal hoort onthoudt, dan is het dit:

Anders zijn betekent niet dom zijn. Het betekent uniek zijn. Het betekent een brein dat is ingesteld op bepaalde manieren van denken, op bepaalde manieren om de wereld te bekijken die anderen misschien over het hoofd zien. En soms is die uniciteit precies wat de wereld het hardst nodig heeft.

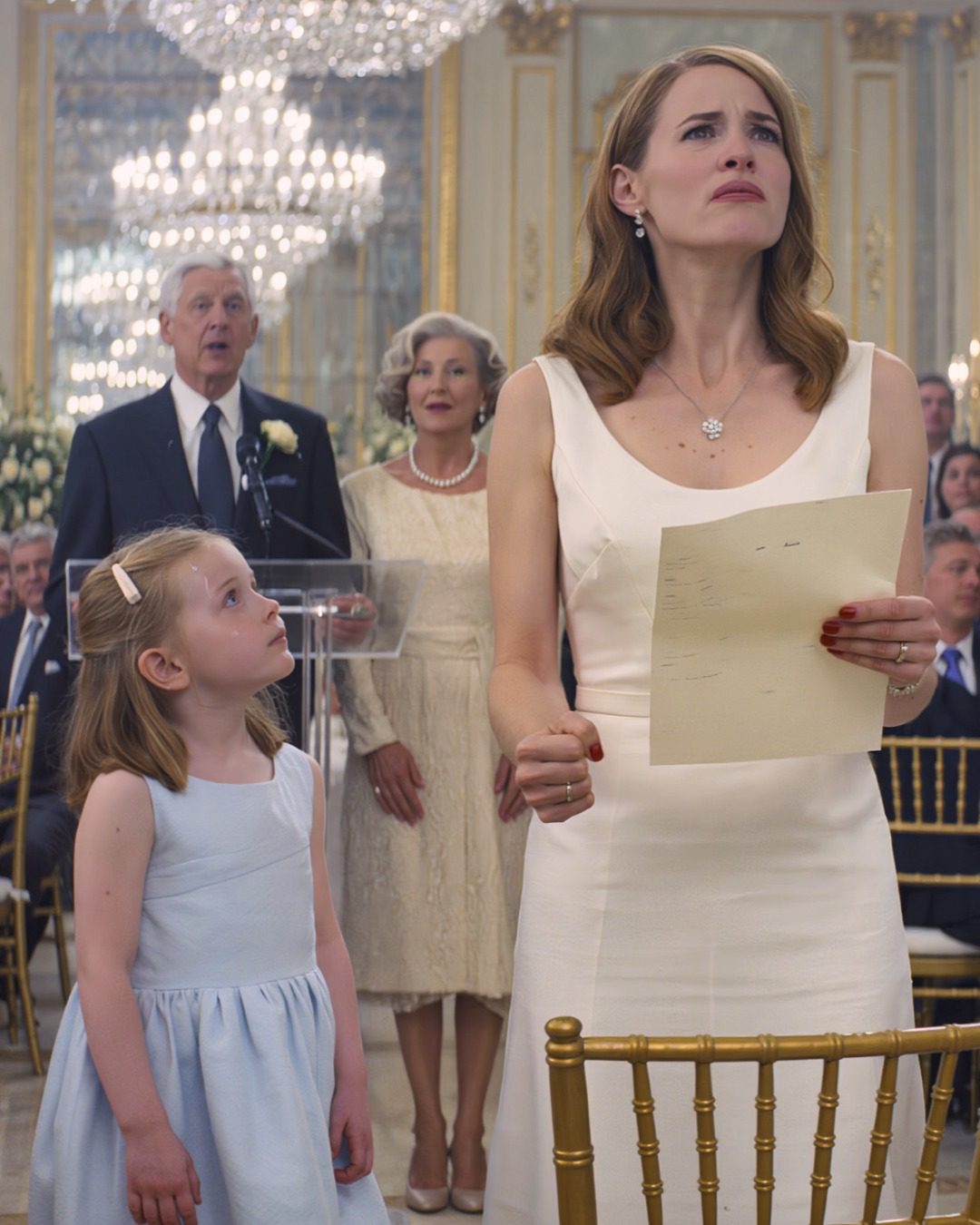

Vraag het maar aan het kleine meisje in de blauwe jurk dat ooit op een feestje voor ‘de domste’ werd uitgemaakt—

En nu helpt hij mee om uit te zoeken hoe we het water in de wereld een beetje schoner kunnen maken, filtersysteem voor filtersysteem.

EINDE.